Boston’s first female district attorney showed how far reform can go — and how hard the system resists.

On a bleak Boston morning, Rachael Rollins glided into a municipal courtroom and sat down beside a young assistant district attorney. No cameras. No press release. Rollins introduced herself: “Hi. I’m Rachael, I’m the D.A. What are you working on?”

The chair squeaked, papers slid, and Rollins listened. To her, this was the real work of reform: showing up where the furniture is broken, where pens are missing, where people have long accepted dysfunction as the price of survival. The broken chair wasn’t just a chair. It was the whole prosecutorial culture she’d been elected to question and challenge – an office and a system that too often accepts cruelty as justice.

A Power Few Understand

“There’s no one more powerful than a prosecutor,” Rollins says, which seems like bragging until you remember she’s right. Prosecutors decide who gets charged, how harsh those charges will be, whether someone sits in jail or goes home. They are the quiet architects of the docket. Every plea bargain, every bail motion, every life shoved and forced through the system carries their signature.

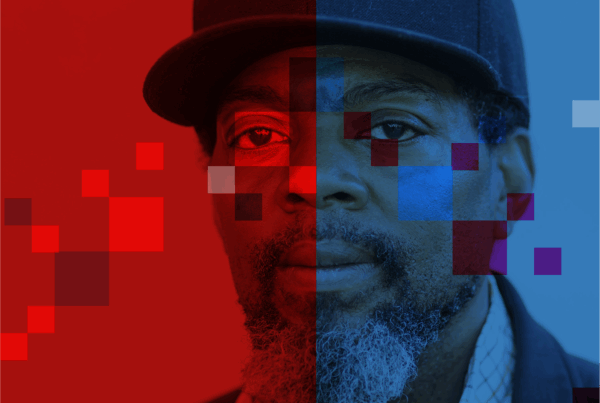

”There's no one more powerful than a prosecutor.

Rachael Rollins

Trials are basically a myth. More than 90% of cases end in plea deals – the result of hasty, off-the-record negotiations where defendants are reminded that freedom is fungible. These deals are often struck before defendants receive full discovery – the evidence and information the prosecution is required to share to support their charges – and often before any formal discovery has been provided. People stuck in pretrial detention plead out 46% more often than those released, according to a 2018 study in the Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. They do it faster, too, because a week in a filthy cell is more persuasive than any courtroom argument. Prosecutors know this. Some even weaponize it.

This is the harm baked into the courts: routine, bureaucratic, unremarkable harm. This is the machine Rollins wanted to reform.

How She Got Here

Rollins didn’t grow up dreaming about becoming the face of this machine. She was the oldest of five kids in a working-class multiracial family where fairness wasn’t a lofty ideal but a daily negotiation. She first thought seriously about law in college when her women’s lacrosse team got axed while the men’s mediocre football team stayed intact. A threatened Title IX suit won them their team back. Lesson learned: if you want fairness, you must fight for it and sometimes you need a good lawyer.

The deeper education happened at home. Rollins watched her brothers enter the juvenile system. She sat in courtrooms where most of the defendants were Black or brown and everyone in power was not. Later, after years at a big firm and as a federal prosecutor, she got tired of complaining about it. She ran for district attorney instead.

The Campaign Nobody Thought Would Work

In 2018, Rollins ran with her cards facing up. She released a list of fifteen low-level offenses she wouldn’t automatically prosecute: low-level shoplifting, trespass, drug possession. There would be a “rebuttable presumption of dismissal,” when people faced these charges, and options to decline the cases or divert them since the vast majority were dismissed anyway. Her argument was less revolutionary than practical: 70 to 80% of the office’s time was spent chasing these cases while Boston had more than 1,300 unsolved homicides. “If you don’t like this proposal,” she told voters, “please vote for someone else.”

Boston liked it. Eighty percent of voters chose Rollins, making her the first woman elected district attorney in Suffolk County, and the first woman of color ever elected DA in Massachusetts and New England. The win also made her a target.

The Memo and the Machine

Once in office, Rollins dropped the Rollins Memo, a plainspoken blueprint for the mission of her office, including positions on bail and charging decisions. Unlike the typical legalese meant only for insiders, it was written so a twelve-year-old could read it. “That’s the age at which children can enter the juvenile system in Massachusetts.” Rollins noted.

Cash bail, she said, should not be a wealth test. Prosecutors were to default to release unless someone was a real flight risk. Dangerousness hearings – public, evidence-based – were to replace the old backroom bail game.

And it worked. Boston’s homicide rate sank to an over twenty-year low. In 2023, it reported 37 homicides, its lowest number ever since the Boston Regional Intelligence Center began counting. But success never inoculates reformers. The system has antibodies.

Backlash on Cue

Police unions revolted when wrongful conviction reviews started pointing fingers at past misconduct. Judges, often former prosecutors themselves, bristled at reopening old homicide cases. Reporters descended on atypical and rare violent incidents as if to prove her policies were a mistake.

“People are often terrified of the new,” Rollins says. “They don’t know how it’s going to be, even if the status quo isn’t working.”

And it wasn’t just local. Prosecutors’ associations lobbied against her. National campaigns to recall progressive district attorneys or tarnish them in the press gained steam. This was the system protecting itself.

The Toll

Rollins lasted three years as district attorney before ascending to become the first Black woman to serve as U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts and New England. There, the pushback sharpened. She tried to press the Department of Justice on its own inequities and hypocrisy, but found herself battered by the same exhaustion, the same suspicion. “If I’d been better at shutting up and not calling out injustice, who knows what office I would hold right now,” she said. “But silence would have been selfish and disingenuous. The people who elected me to be D.A. and saw themselves in me as U.S. Attorney deserved more.”

Fragile Change

After resigning from the U.S. Attorney’s office in 2023 amid allegations of misconduct, Rollins retreated from the political spotlight but not from the work. She created and now runs a program at Roxbury Community College that helps people impacted by incarceration rebuild their lives through education and social, emotional and experimental learning programs. The role circles back to the reasons she entered law in the first place: seeing the people the system too often ignores or discards and insisting they deserve more. It is not the kind of power she once held, but it is the kind of presence she knows matters.

Rollins’s record is undeniable – more than 400 years of wrongful convictions undone, bail reform, record-low homicides, New England’s first federal civil rights and human trafficking unit. Still, her reforms remain provisional, always at risk of reversal.

The broken chair is no longer in that municipal courtroom. But defendants still file in, destined to accept pleas rather than trials, especially if they’re detained in jail. Ending that will require more than one district attorney’s term. It will require a country willing to see the violence hiding in plain sight – not just in the streets but in the courts, where coercion can masquerade as justice.

We need your help to secure freedom for people trapped behind bars because of unaffordable bail.

Your support gives hope to the thousands of people still trapped in pretrial detention. We’ve supported more than 40,000 clients through free bail assistance and community-based support services like affordable housing and healthcare, and mental health services. You can help secure the freedom of thousands more.

The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you.