This fall, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office’s practice of posting arrested people’s mugshots online amounts to illegal pretrial punishment and is unconstitutional. The ruling – which bars the Sheriff of Maricopa County from making these mugshots publicly available – sets a precedent not only for other states, but also local newsrooms and their approach to covering crime.

“The result is public exposure and humiliation of pretrial detainees, who are presumed innocent and may not be punished before an adjudication of guilt,” Judge Marsha Berzon wrote in an opinion published in early September.

Before the ruling, police agencies across the country routinely posted photos of people being processed in its jails on the internet. Newsrooms would often follow suit and repurpose these mugshots by quickly churning them out into short stories or photo galleries.

The presumption of innocence – the idea that everyone in the United States is innocent until proven otherwise – is turned on its head by these mugshots. Like pretrial incarceration itself, the existence of a mugshot can be perceived by some as evidence of guilt, despite the fact that mugshots are taken at the time of arrest, before formal charges have even been filed and well-before an individual has had their day in court.

Because mugshots are ubiquitous in the media, many may not have given full consideration to the consequences of sharing those images. But the consequences are real – and lasting.

Because mugshots are ubiquitous in the media, many may not have given full consideration to the consequences of sharing those images. But the consequences are real – and lasting.

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeal’s ruling stems from a lawsuit filed by Brian Houston, a Phoenix resident whose mugshot and personal details were posted online for three days in 2022.

Despite being legally innocent, the sheriff’s department posted Houston’s image alongside his full name, birthdate, sex, weight, height, and other personal information – including the alleged offense on which he was arrested – only for prosecutors to later dismiss his case and drop the charges altogether.

But by then it was already too late. The emotional and mental toll of being publicly humiliated left Houston feeling exposed and vulnerable. He’s not alone. Countless Americans are forced to wonder whether an old mugshot will impede their chances of getting a job or renting an apartment in a highly competitive job and housing market.

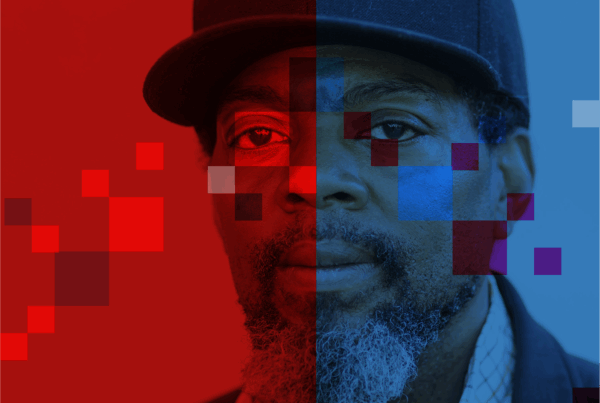

Like almost everything else in the criminal justice system, the burden of mugshots is borne most heavily by communities of color. Because Black people are disproportionately arrested and those arrests are disproportionately covered by the news media, many of the mugshots that appear in the news are of Black people. These images, like the stories they appear in, prime negative racial stereotypes.

Given all the harm they cause, it’s important to take a step back and ask: why do police and journalists need to publish people’s mugshots in the first place? It is one thing for this information to be available within the inner chambers of hard-to-access government databases, and quite another for it to be available to thousands of viewers during evening news broadcasts, in digital mugshot slideshows, and in the endless scroll of social media feeds.

Thankfully, many news outlets have grappled with this question in recent years and begun to change their ways. Newsrooms across the country have curtailed their use of mugshots as part of a larger effort to reconsider the ways in which people and communities of color are portrayed in the media. Some news organizations and police agencies have even made the decision to stop posting photos of people who have been arrested but not convicted altogether in recognition of the presumption of innocence.

Which brings us back to the recent 9th Circuit ruling. This decision is more than just a new rule for government officials to follow. It’s a challenge and an invitation for journalists to reconsider a corrupt cornerstone of crime reporting and chart a new path forward that better reflects the goals and values of journalism.

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.