Former appellate judge Pierre Bergeron has spent years reviewing bail hearing decisions, where a judge decides whether the accused should await trial in jail or be released. He served on Ohio’s First District Court of Appeals, where he participated in more than 1,000 cases. In a recent conversation, Bergeron outlined how bail decisions are typically made, what challenges judges face, and how the system can be improved.

Judges Often Decide Bail with Minimal Information

Many people assume that judges rely on a thorough presentation of evidence to make pretrial decisions. In bail hearings, however, that is often not the case.

“Most of the time, no evidence is introduced at all.”

According to Bergeron, trial judges frequently make pretrial decisions based on arguments from attorneys rather than on actual evidence. “Most of the time, no evidence is introduced at all,” he said. “You hear from the prosecutor and the defense, but they are not presenting documentation or calling witnesses.”

The limited time judges have to consider each case is a major factor. Bergeron noted that trial courts are often overloaded and backlogged with cases, leaving judges with little time and making it difficult for judges to conduct detailed evaluations of each individual’s circumstances. The result, he said, is a system that relies more on routine and intuition than on a clear assessment of risk or fairness.

Pretrial Detention Without Bail is Possible, But It Is Rarely Used

In most states, for serious cases, courts may deny release entirely and keep an individual in custody until trial. According to Bergeron, this option is used far less often than one might expect. Instead of holding a detention hearing, judges will frequently set very high bail amounts that are effectively impossible to pay. “A two-million-dollar bond is not intended to be met,” Bergeron said. “It functions as a form of detention without the formal process.”

”A two-million-dollar bond is not intended to be met. It functions as a form of detention without the formal process.

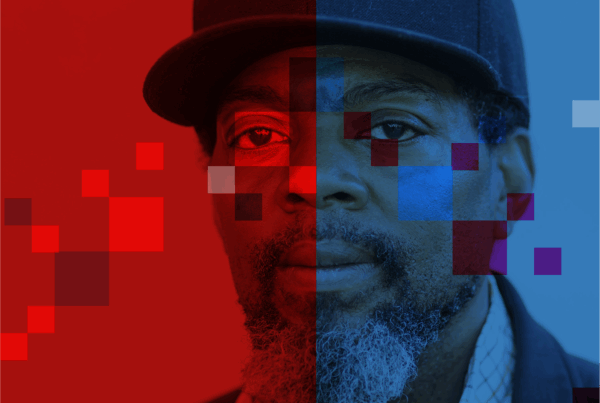

Pierre Bergeron

He argued that if prosecutors believe someone poses a danger to the community or is unlikely to return for trial, they should make that case. However, the process takes time, resources, and a willingness to present and examine evidence – steps that many courts and prosecutors are reluctant to take.

Pretrial Detention Encourages Plea Deals

A major concern among reform advocates is that pretrial detention often compels people to accept plea deals, regardless of their guilt or the strength of the case against them. “If someone is sitting in jail, especially for a low-level offense, and they are given a chance to walk free by signing a plea agreement, they are likely to do it,” he explained. The pressure to get out – whether to return to work, care for children, or maintain housing – can outweigh the desire to challenge the charges.

Judges Lack Access to Data

Another problem, Bergeron argued, is the lack of infrastructure to help judges make informed decisions. Courts often do not have access to data on what happens when individuals are released without bail or how often they return to court – a fact that was surprising to Bergeron himself.

“I assumed there would be a trove of data we could analyze to see what works. Instead, I was told it doesn’t exist.”

“I assumed there would be a trove of data we could analyze to see what works,” he said. “Instead, I was told it doesn’t exist.”

Toward a More Equitable System

When asked what changes he would make to the pretrial system, Bergeron emphasized the need for more individualized assessments. Judges, he said, should have the time, information, and resources to consider each defendant’s circumstances, rather than relying on quick decisions and high bail amounts.

He also called for greater investment in community-based programs that provide housing support, treatment, and case management. These services, he argued, not only reduce the risk of reoffending but also make judges more comfortable releasing people without requiring payment.

Finally, Bergeron stressed the importance of reliable data about the outcomes of judicial decisions. Without it, he said, policymakers and judges are left to operate based on assumptions.

Beyond Good Intentions

With limited information, few resources, and little time, judges are often forced to make quick decisions that have lasting consequences.

Improving this system, Bergeron believes, will require more than good intentions. It will take data, infrastructure, and a shift in how courts define justice before trial begins.

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.