For Lucretia, back-to-school season begins with a question: who will look out for the kids whose parents won’t be there on the first day, whether because they’re in jail or prison? She remembers being one of them, and now she makes sure they’re not forgotten.

I want to give back to the young people. I want them to know that I experienced what they are experiencing.”

“I want to give back to the young people. I want them to know that I experienced what they are experiencing,” she says.

Parental incarceration is a widespread but often overlooked adverse childhood experience that disrupts the educational journeys of millions of children in the United States each year. Roughly 5 million children – 1 in 12 – have had a parent incarcerated, a burden that falls disproportionately on 1 in 9 Black children.

Research shows that children of incarcerated parents face significant academic challenges, from lower standardized test scores and higher dropout rates to increased disciplinary issues and reduced satisfaction with their education. The impact stems not only from the absence of a parent, but also from the trauma, stigma, economic hardship, and family instability that incarceration brings – factors that can derail a child’s well-being and school performance from elementary years through high school and beyond.

Lucretia was nine years old when her mother went to prison. She and her siblings were raised by their grandparents, who never let them miss a Saturday visit to see their mother in prison. Her grandfather made sure they had stamps, paper, pens to write to her. Her grandmother, Lucretia says, also wrote to her daughter every single day. “People at the prison were jealous,” she says with a laugh, recalling how they’d tease her: “‘What kind of mama y’all got up in here?’”

“People would ask, ‘Where’s your mom?’ I’d say she was a traveling nurse.”

But that care came at a cost. Lucretia learned early how incarceration distorts childhood, how silence grows around it and how shame tightens its grip. At school, she lied. “People would ask, ‘Where’s your mom?’ I’d say she was a traveling nurse. Who wants to say their mom is incarcerated?” But she also learned what makes a difference.

She found community beyond her family in a local program that served children of incarcerated parents – then called Aid to Children of Imprisoned Mothers, now known as Foreverfamily. “We were the first family to be served,” she says. Every second Saturday for five years, the program took her and her siblings to visit their mother, giving her grandparents a rare weekend of rest. “That open communication was everything,” she says. “Even though my mom was incarcerated, we didn’t care. We still wanted to talk to her.”

The program didn’t stop at visits. Lucretia and her siblings were enrolled in after-school programs and attended summer camp every year. She was mentored by the organization’s founder, a former public defender who left law to start the nonprofit after hearing mothers in jail say what they missed most was seeing their children. “She’s been my mentor ever since I was nine years old,” Lucretia says. “She came to my wedding. She was at my mom’s funeral. And she’s still in my life today.”

That mentor helped shape Lucretia’s path, pushing her professionally, encouraging her to practice public speaking through Toastmasters, even helping her change her wardrobe and apply for leadership programs. “She helped me grow up,” Lucretia says. “And I just wanted to give other kids what I was given.”

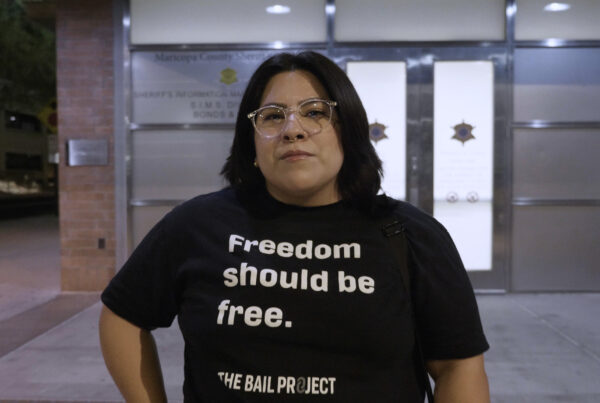

Her job as a bail disruptor for the Atlanta site of The Bail Project brings her even closer to the issue. Every day, she talks to clients. Many are parents eager to get home, frustrated by missed milestones, desperate to be present. “I tell them, ‘You missed the first day of school. You missed the pictures. You can’t get that back,’” she says. “But we can move forward.”

“I let them know, my mom did five years in prison. And they open up to me.”

When she meets fathers, she refers them to partners who provide parenting support. When she meets mothers, she shares her own story. “I let them know, my mom did five years in prison. And they open up to me.”

She knows the ripples firsthand. “Everybody is suffering – the caregiver, the children, and even the person that’s incarcerated. They can’t go to P.T.A. They can’t go to the recital. They feel ashamed.”

The stakes stretch far beyond not having school supplies. “Children with incarcerated parents are more likely to be incarcerated,” Lucretia says. “I’m trying to change that whole stigma, pretty much.”

A few years before joining The Bail Project, Lucretia launched the Patricia Ann Doyle Foundation – named for her mother – a nonprofit dedicated to supporting children of incarcerated parents. At first, it was small: college book scholarships of $250, some toiletries, a few Christmas gifts. But over the years, her grassroots operation has grown into a deeply personal support system for children with incarcerated parents.

The Foundation’s work continues to this day. This year, she supported eight children preparing to go back to school. “I had one toddler, we helped pay for daycare for two weeks. I had a middle schooler that we helped go to camp, STEM camp. He went to robotics one week, and math camp the next. He’s going to a charter school that’s geared toward his learning. He loves to build. He loves to read and write. And the camp loved him so much, they gave him another week for free. I told his family, ‘That’s favor. Favor ain’t fair.’”

Lucretia doesn’t do this work to be recognized but the recognition has come anyway. This summer, she received the Level Up Day Champions Awards in Gwinnett County, where she operates PAD. It was in recognition of her commitment to serving the community and creating lasting change. “Our name is hitting the rooms in different spaces,” she says, quietly proud. “And it’s my mom’s name. That’s the beautiful thing.”

What Lucretia’s work for The Bail Project and the Foundation offers isn’t just financial support and supplies, but something bigger. “I truly believe every child deserves some type of program or mentoring initiative,” she says. “It does take a village to raise children, especially children who have a parent that’s incarcerated.”

Asked what motivates her most, she doesn’t hesitate.

“I just want these kids to have the best,” she says. “No child should feel alone.”

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.