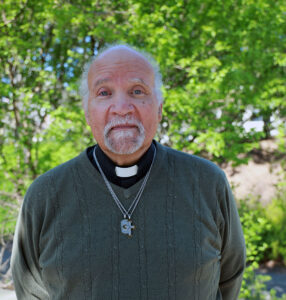

Reverend Charles Tinsley is a minister and juvenile justice advocate. Over the last five decades, he’s spoken to hundreds of incarcerated youth, listening to their struggles, learning about the challenges they’ve overcome, and supporting their goals. For 24 of these years, Rev. Tinsley helped youth in juvenile detention facilities apply to colleges, find jobs, and advocated on their behalf in court. For him, it’s not just a profession – it’s personal: he legally adopted two children and serves as a surrogate parent to countless others, many of whom are without loving parents.

In 2005, when Rev. Tinsley was working as chaplain of Contra Costa County’s Juvenile Hall, he was introduced to Ryan, a 17-year-old resident of a nearby juvenile mental health care facility. Ryan had been placed in foster care as an infant after his mother, who battled drug addiction, was incarcerated and lost custody of him. Over the next 18 years, Rev. Tinsley supported Ryan in any way he could. He paid for his college tuition, housing, and found him a job. In doing so, Ryan felt a sense of belonging.

Despite these achievements, Ryan’s painful childhood memories and mental health symptoms overshadowed his judgment, causing him legal problems. Rev. Tinsley despaired as he watched Ryan become justice-involved after becoming an adult. He tried to advocate for Ryan’s release and reduced sentences, but with limited money and access to resources there were limits to how much one person could do. “I love Ryan as a son and I want what is the very best for him,” Rev. Tinsley said in a letter to a judge. “I maintain time spent in a mental health care facility could potentially be more beneficial for him, and for the community, than in a jail where treatment is beyond the institution’s scope.”

Rev. Tinsley soon realized that Ryan was the most work-intensive individual he ever cared for. In order to help him, Rev. Tinsley would need the support of his community, network of givers, and nonprofit organizations, such as The Bail Project. This experience not only deepened Rev. Tinsley’s commitment to cash bail reform, but also reaffirmed his belief in the positive role charitable bail funds have in communities.

“The criminal justice system takes advantage of people who don’t have the social bandwidth to take them on. There’s people who are incarcerated that could be easily [released] if they had the money,” Rev. Tinsley said.

“Many people in my network have been helping me from the very beginning. I still use that network today.”

In the late 1980s, Rev. Tinsley recognized that incarcerated youth face many disparities that he understood to be the result of significant underfunding of critical supportive services for populations and communities most in need. To address gaps he saw, and recognizing the additional assistance he could provide as a faith-based leader, Rev. Tinsley went to work establishing partnerships with other faith-based leaders and social service providers so that together they could form a tapestry of care: Where government services struggled to meet these needs, the community would step in to help people, including those who were released pretrial get access to the services they needed most. His wide-reaching network of volunteers paid tens of thousands of dollars for food, housing, clothes, eyeglasses, and college scholarships. Many of the volunteers he worked with also provided community service opportunities for formerly incarcerated youth. Unwilling to abandon people who had become justice-involved, those in Rev. Tinsley’s network welcomed them into their homes to meet with friendly people interested in providing care and community support.

According to Rev. Tinsley, some of the most vulnerable adolescents he helped raise were individuals like Ryan, who grew up in foster care because either one or both parents were incarcerated. There are an estimated 5 million children in the United States with at least one incarcerated parent. The impacts of parental incarceration on life outcomes is stark: many experience lower educational attainment and higher dropout rates; many struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder and other behavioral difficulties; they also face a greater likelihood that they will become justice-involved themselves at some point in the future.

The disadvantages imposed upon children and adolescents with incarcerated parents is compounded by foster care placements, where they are commonly subjected to mistreatment and neglect. Foster care placement alone, without parental incarceration, has significant impacts on a child’s future outcomes and success. Ryan spent a significant portion of his childhood in group homes throughout Marin County, CA, where he was subjected to physical and emotional abuse. “Sometimes I was hit,” Ryan said. “You saw grown adults restraining kids. They had padded rooms where they strapped you to the bed if you acted out. My first time in one was when I was eight-years-old.” Doctors diagnosed Ryan with bipolar disorder and PTSD, which is not uncommon for children who grow up in foster care or who have incarcerated parents.

Ryan’s teen years included institutions as well. When he was 17, he was placed in a juvenile mental health care facility in Contra Costa County, CA. As a minor, he lacked the legal authority to leave on his own. With his mother incarcerated, and few family members to care for him, Ryan existed without the type of kinship care people sometimes take for granted. “I was in the start of severe depression. I had a complete loss of hope of any kind [for a] happy future,” Ryan recalled. “I was so used to people abandoning me.” He worried about what his future would look like, but he knew one thing – as soon as he turned 18 and was considered an adult, he’d leave the facility.

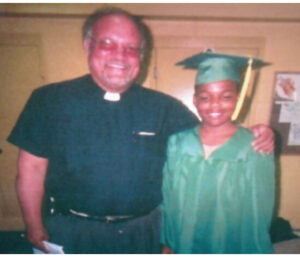

Rev. Tinsley was asked by the assistant director of the juvenile facility to meet with Ryan a few months before his 18th birthday. “I began to speak with him on a regular basis about the idea of going away to college, about what he might wish to do with his life,” Tinsley recalled. Those conversations resulted in Tinsley covering the costs of Ryan’s tuition at a community college in Oroville, CA. Later, Ryan applied and was accepted to Knoxville College, a four-year historically Black liberal arts college in Knoxville, TN, where Ryan could pursue a bachelor’s degree.

Many academics consider educational attainment and employment both to be stabilizing factors that prevent criminal justice involvement. Unfortunately, the upward trajectory of Ryan’s academic career wasn’t enough to provide the stability he needed: he struggled with the symptoms of his bipolar disorder and PTSD, and was kicked out of college after an alleged altercation. After his expulsion, he had difficulty holding jobs. Without school or a job, Ryan’s legal troubles began. For the better part of the next decade, he cycled in and out of jail, where on several occasions, he was placed in solitary confinement, which is known to be especially harmful to people who have been diagnosed with serious mental illness.

Rev. Tinsley worried about Ryan’s well-being behind bars. He wrote more than a dozen letters to prosecutors, judges, sheriff’s departments, and district attorneys advocating for Ryan’s release and pleading that incarceration for him was not only unnecessary, it was also unsafe and detrimental to his future stability. Rev. Tinsley had other religious leaders write letters for Ryan, too. Despite their efforts, Ryan remained incarcerated. “Stories of torture and death, at the hands of fellow inmates and guards abound and are numerous,” Rev. Tinsley wrote of Ryan in a 2014 letter to Marin County’s district attorney. “I do believe that sending him to prison is tantamount to signing a warrant for his death.”

In 2018, Rev. Tinsley retired from his work with the Juvenile Hall and moved to southwest Ohio, where he currently serves as chaplain for National Church Residences. A few years later, Ryan, who was now in his early 30s, decided to follow and moved to Montgomery County, Ohio, at Rev. Tinsley’s suggestion. About a month after arriving, police called Ryan and said there was a warrant out for his arrest. Ryan was still on probation and busy settling in his new apartment. He was surprised and figured it must be a mistake. It wasn’t.

On October 7, 2021, Ryan was arrested and booked into Hamilton County jail. His bail was set at $25,000. Inside jail, Ryan’s mental health took a turn for the worse and correctional staff decided to place him in a solitary cell. There were no windows or clocks. He was allowed outside for only a few hours each day. Ryan was deprived of food and felt claustrophobic. “Being in isolation makes a person’s mental health worse,” Ryan said. “I was losing weight and I kept telling [the correctional officers]. After the [nurse] looked at my chart they finally realized I was right and they suddenly showed up with 10 apples.”

Ryan said he considered filing a complaint, but ultimately decided against it. “All you can do is write grievances and see if they do an internal investigation,” he said. “But that never goes anywhere. It’s impossible to hold someone accountable.”

Despite the lack of appropriate mental health care in correctional facilities, America’s jails and prisons have become the de-facto healthcare providers for people incarcerated with mental illnesses. Approximately 44% of people incarcerated in jails — or about 2 in five people — have been diagnosed with a mental illness. Without enough state hospital beds or community-based care options, nearly two-thirds of people with mental illnesses in jails fail to receive proper medical treatment. Unable to advocate for themselves or effectively express their needs, this vulnerable segment of the incarcerated population are trapped behind bars with no access to the outside world.

“When I found out what happened to Ryan, that’s when I contacted The Bail Project’s office. I met with Jeremy Page and took him out to lunch,” Rev. Tinsley said, referring to The Bail Project’s Operations Manager for Ohio. “I was quite impressed with him. I was immediately supportive. ”

After interviewing Ryan, The Bail Project paid his bail and he was released from jail. Ryan received free Lyft rides to and from court to help ensure that he could easily attend his future court appearances. The Bail Project’s staff also referred him to social service providers so he could see a doctor and therapist. Over a year later, Ryan’s case was finally resolved – prosecutors dropped his charges due to lack of evidence.

Rev. Tinsley sensed a certain synchronicity in the timing of his learning about The Bail Project and Ryan’s incarceration. Every day, across the United States, there is someone incarcerated simply because they cannot afford to pay the bail amounts set against them. Approximately one out of every three clients The Bail Project serves are like Ryan – their cases are ultimately dismissed after some period of incarceration that occurs because bail is set at amounts they cannot afford. Had Rev. Tinsley and The Bail Project not intervened, Ryan would have remained incarcerated unnecessarily for a year simply because he could not pay the bail amount set against him. Ryan would have lost his apartment, car, and job painting houses.

On days when Rev. Tinsley worries his goals seem out of reach, he reminds himself of the promise held by organization’s like The Bail Project to show up in unexpected ways to support people in their communities. “Having hope and being able to bounce back from these experiences is important,” Rev. Tinsley said. “There also needs to be accountability. So much has been done to Ryan. It is unjust.”

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.