A quiet storm has settled over the American criminal justice system – one that doesn’t announce itself with a gavel or a jury verdict, but with the rustle of a file being closed. Dismissals. On the surface, they suggest justice has prevailed. But for those who’ve lived through it, they reveal something more troubling: a system that punishes before it proves, detains before it decides, and coerces outcomes long before a trial begins.

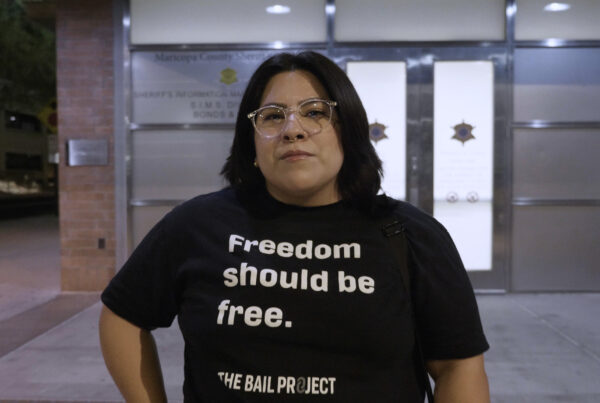

Karima knows that story intimately. She spent years helping others navigate the system – working with youth on probation, managing foster care cases, and running intervention programs. But in a sudden, disorienting turn, she became the defendant.

It began with a traffic ticket and ended with three arrests, an involuntary psychiatric hold, and the loss of her job.

Karima had been on vacation when her father received a camera-issued citation while driving her car. The vehicle was still registered in her name. When she returned and told him he could no longer use it, a family dispute turned physical. Her father filed for a civil protection order, which was granted without a hearing, without Karima present to offer her side of the story.

That order gave him exclusive use of the car and barred her from evicting him from the two-family home they shared. It became the basis for her first arrest: Karima was taken into custody after attempting to return home, unaware that returning to their shared property – but separate dwellings – would be considered a violation of the protection order.

“I remember telling the judge, ‘I’m not a criminal. I have zero criminal charges.’”

In the weeks that followed, she was jailed twice more for violating the protection order with terms Karima says she didn’t understand at the time. She wore an ankle monitor for a time and endured court supervision. “I remember telling the judge, ‘I’m not a criminal. I have zero criminal charges,’” she says. “But it didn’t seem to matter.”

All charges were eventually dismissed in her case. There was no trial. No conviction. “They don’t even say, ‘our bad,’” she notes. “They skip that part entirely.”

Across the country, these silent dismissals happen often. Approximately one-third of cases where The Bail Project is involved are dismissed outright – with some counties seeing rates above more than 50%. These numbers aren’t signs of a fair system; they’re warnings. People are arrested on shaky evidence or hunches, charged aggressively, then discarded when the state has no case.

Pretrial detention, especially for those who can’t afford bail, ensures punishment comes early. People lose jobs, homes, and custody of their kids. They miss school. Bills pile up. Their lives unravel before they ever get a chance to speak in court. The median time The Bail Project’s clients spend in jail before release is 15 days – longer in places like Fulton County, Georgia and Phoenix.

“I didn’t know what that felt like, to sit inside of a cell and realize: I can’t leave.”

“I didn’t know what that felt like, to sit inside of a cell and realize: I can’t leave. I have to go to work tomorrow. I didn’t do anything to anyone,” Karima says.

And the pressure doesn’t stop after release. People are simply moved into another kind of limbo. The average case length for Bail Project clients is six months, sometimes more than a year. During that time, defendants often can’t work or travel freely. They live in fear, constantly calculating the risks. This is where plea deals enter the picture – not as a real choice, but as a way out.

“And that’s why the plea deals are so tempting,” Karima explains. The longer a case drags on, the harder it is to hold out – emotionally, financially, spiritually.

Dismissals don’t mean the system is correcting itself. They expose how bail and detention become tools of coercion – pressuring people to accept a conviction just to get their lives back. Guilt or innocence becomes irrelevant. Endurance becomes everything.

Karima now works for The Bail Project in Cleveland as an operations manager. She helps people navigate the very system that nearly crushed her. For her, the high dismissal rates in places like Cuyahoga County (24%) and nearby Hamilton County (33%) don’t mean justice is working – they mean the system is overcharging and overreaching.

“All of those things were to prepare me for this.”

Her own ordeal became the training ground no classroom could provide. “All of those things were to prepare me for this,” she reflects. The trauma now fuels her work. She sees her story in her clients’ every day.

She recalls one man arrested for felonious assault after using a knife in self-defense during an argument. Police charged him, and he spent two days in jail before Karima paid his bail. A public defender then sent an investigator to gather evidence. Witnesses confirmed the client’s version, and the prosecutor dropped the case before indictment. This, Karima says, is the kind of defense that only exists with access to resources. Most people never get that chance.

Another case involved a client with schizoaffective disorder. During a manic episode, he threatened his father. Police arrested him, but the father didn’t want charges filed – he just wanted his son stabilized. Karima worked to get him released, but had to navigate a no-contact order, the kind judges often impose by default in any case involving a victim. Such orders, meant to prevent further harm, can end up blocking the very support families want to give. “You can’t be a victim and a defendant at the same time,” she says, noting how the system’s rigidity often conflicts with what families actually need.

“People want to tell you what happened.”

She sees this contradiction constantly – where rules meant to protect end up harming. And where courts move quickly without listening much to the defendants, she offers something rare: someone who will hear them out. “People want to tell you what happened – not because they think it will change their case, but because no one’s asked.”

That’s where she meets them. With care. With context. With the belief that people are more than their worst day.

Her resolve is fueled by purpose and faith – and by the moments when clients, moved by simple dignity, begin to cry. “That’s when I know,” she says, “that I’m doing what I’m supposed to do. To be a light in a dark place. To help set the captives free.”

Karima’s story isn’t exceptional. It’s a reflection of a system that mistakes accusation for guilt, that measures efficiency in dismissals and plea deals rather than real justice. Her charges being dropped didn’t mark the end. They marked the beginning of something else – a reckoning, a calling, a redirection of her life’s work.

Her presence at The Bail Project is more than professional. It’s personal. Every person she helps is a reminder of what the system takes – and what it can never return. A dismissal may close a file, but it doesn’t restore a job, repair a reputation, or erase the memory of a locked door.

The system may never say sorry. But Karima does – through her actions, her advocacy, and her unwavering belief that every person deserves to be seen. And heard.

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.