William was walking down the hallway in the St. Louis County courthouse one late September afternoon in 2023, when he bumped into Jessica Boggs, a first-appearance attorney with the MacArthur Foundation. It was the first day of a new pretrial pilot program that encourages judges to release people without cash bail. Jessica looked eager to speak to William.

“We got a judge to release someone on recognizance,” she said.

William, who is The Bail Project’s Operations Manager in St. Louis County, sped over to the courtroom. Inside, he spotted Trevor,* a male defendant in his mid-20s, sitting inside a secured area. The young man was wearing an orange jumpsuit and his hands were shackled at the wrists. “I’m here to help you,” William said, as he pulled out Trevor’s case files to review.

William was there to ensure that Trevor – and anyone else in that courthouse who a judge decided to release on their own recognizance – had all the information and resources needed to successfully return to future court dates.

“I noticed you failed to appear at one of your previous court dates,” William said. “Is that right?” Trevor nodded yes, and said it was an accident. “I was in the middle of moving and was living with my girlfriend at the time,” Trevor explained. “I wasn’t able to get my mail, so I didn’t know I had court.”

William told Trevor that he could update his address with the courthouse and that, if he’d like, he could also have The Bail Project send him text message court reminders, provide him free rides to court, and refer him to voluntary supportive services. Trevor agreed to participate. William smiled, knowing the services could help. The judge finalized everything and told Trevor he was free to go home without any of his own money on the line.

Much is at stake when people are required to pay money in exchange for their release from jail. Trevor could lose his job or home if he had to sit in jail while his case remained open. Over the years, William, a 55-year-old St. Louis native, witnessed mothers and fathers lose custody of their kids because they were too poor to afford bail. He’s also watched innocent people take plea deals just to escape harsh jail conditions.

“Courts want a cash bail system because there’s the belief that if people don’t have any monetary skin in the game, then they won’t come back. But we’ve already proven that isn’t true.”

“Courts want a cash bail system because there’s the belief that if people don’t have any monetary skin in the game, then they won’t come back,” William said in a recent interview. “But we’ve already proven that isn’t true.”

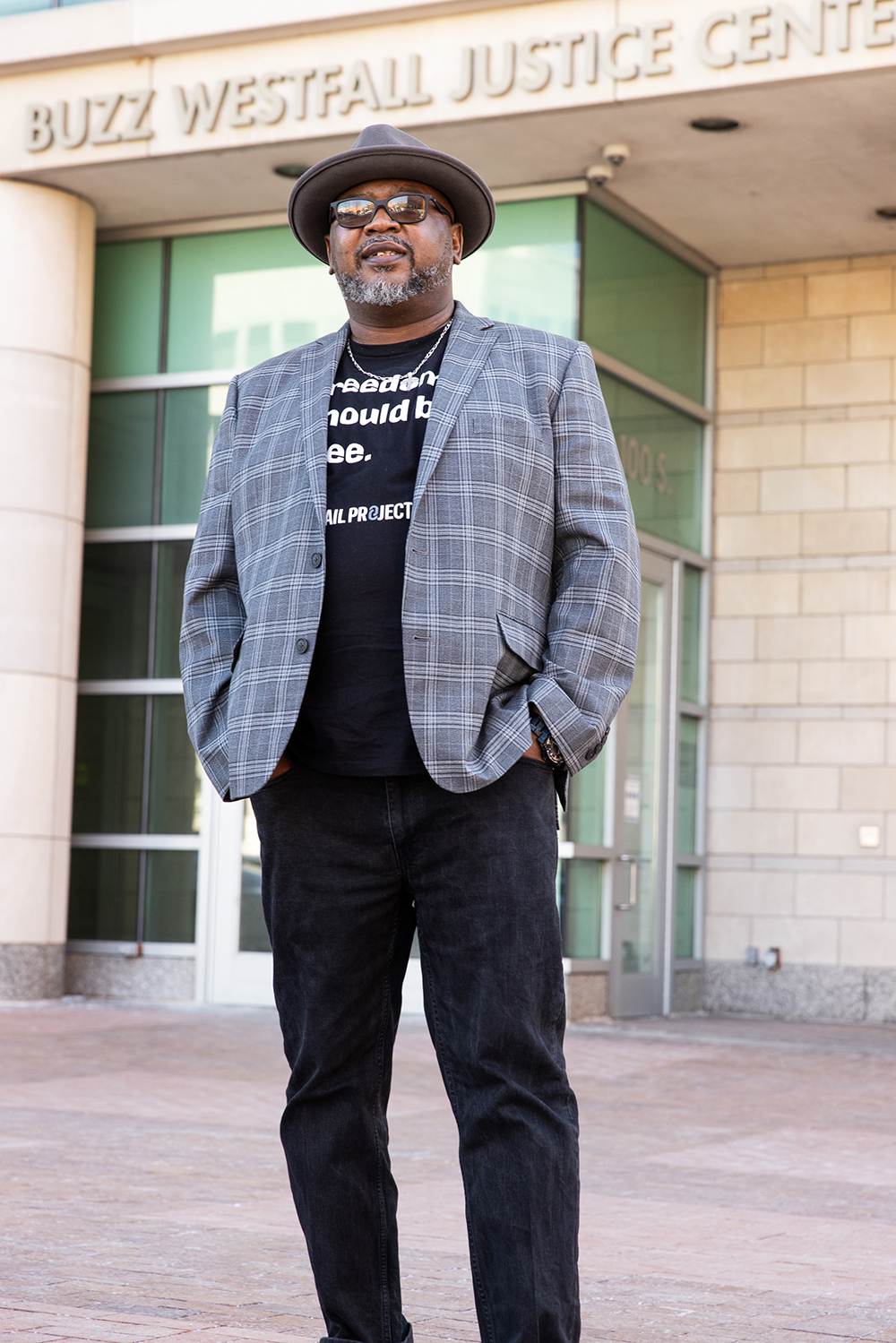

William has dedicated the last two decades of his life to fighting for criminal justice reform – the last three years of which he’s spent working to end wealth-based detention with The Bail Project.

Today, in addition to leading a four-person team at The Bail Project, William spends most days working inside one of two courtrooms at the St. Louis County Courthouse, supporting justice-involved people, like Trevor, during their arraignments.

Today, in addition to leading a four-person team at The Bail Project, William spends most days working inside one of two courtrooms at the St. Louis County Courthouse, supporting justice-involved people, like Trevor, during their arraignments.

William’s enthusiasm, curiosity for others, and contagious smile is hard to miss. Over the last year, he’s become a permanent fixture at the St. Louis County courthouse. During his work breaks, he often roams the hallways there, mingling with prosecutors, bailiffs, and other court staff. Sometimes, he grabs coffee or lunch with judges. And on special occasions, he brings donuts for everyone to share — always remembering which ones are people’s favorites.

But if there’s one thing people who work there have yet to learn about him, it’s this: for William, returning each day to the St. Louis Courthouse means more than simply going to work. It’s a reminder of how far he’s come in life.

Decades earlier, in one of the second floor courtrooms, a judge sentenced William, who was 26-years-old at the time, to four years in prison. In the months leading up to his sentence, William’s life was fraught with unease and despair: although a judge had determined that he was eligible for pretrial release, William’s bail was set at an amount he couldn’t afford — $20,000. Because he didn’t have the money to pay bail, William was incarcerated at a county jail, where he was confined to his cell for up to 23 hours each day. If his financial situation was different, he could have gone home.

Deprived of almost any human contact while incarcerated, William was alone with only his thoughts to keep him company. Months passed without him feeling sunlight on his skin. He longed to speak to his loved ones and worried that he’d soon forget how they looked. What William missed most was being a father to his newborn baby daughter. He tried convincing himself that soon his case would go to trial and that life within the confines of his small cement cell was only temporary. But after more than two months of living in isolation, William was unable to withstand it any longer: he agreed to take a plea deal.

“People who are in these situations often make the decisions that they do because they’re desperate.”

“People who are in these situations often make the decisions that they do because they’re desperate,” William said about the pressures he and others feel when presented with plea bargains. “I hadn’t seen the sunlight in two months. My skin changed. So when [prosecutors] come to you with this deal…you’re thinking about how you’d do anything if it means leaving.”

On September 13, 1996, William stood before a judge and agreed to a plea deal which included a four year prison sentence. As officers took him into custody, William vowed never to set foot in that courthouse again. But on a cold September day, almost 28 years later, William returned – only this time it was to work alongside those same judges, prosecutors, probation officers, and public defenders in an effort to reform the pretrial and criminal justice system.

“Now [that] I have the privilege of being able to sit at the table, I feel like I bring a voice to the conversation that these people otherwise might not understand,” William said.

William’s perspective, as many stakeholders in St. Louis learned, is crucial to have. Ten years ago, his hometown became the epicenter of America’s rallying cry against inequity and racism in the criminal justice system after Michael Brown, a Black 18-year-old, was shot dead by a white police officer in the streets of Ferguson.

Today, many people feel that momentum for social progress has stalled or been reversed. However, William’s work demonstrates that incremental change continues to be made. That he helped spearhead such a collaboration between judges and advocates in reforming Missouri’s criminal justice system is one example of how long-lasting change can be achieved.

“I like to tell people that this is the building where I was convicted, and that somebody they locked up is back in front of them and doing very good work,” William said, referring to the St. Louis County courthouse.

While most people prefer keeping their personal and professional lives separate, for William, merging his personal and professional worlds into one has proved to be his source of strength and creativity.

He grew up during the 1970s in Walnut Park East neighborhood, a working and middle-class suburb of St. Louis. While most of St. Louis County is white, William’s hometown and neighboring areas are predominantly Black. Only five miles away is Ferguson.

After leaving prison, William spent the first part of his career supporting formerly incarcerated fathers entering back into their communities. The work was deeply personal and meaningful for William; witnessing fathers go on to lead productive and successful lives with their families encouraged him to reconnect with his own father. The pair eventually forged a close bond, and before William’s father died, he considered him his best friend. His work also felt rewarding from a public policy perspective. To him, it served as direct evidence of the impact local governments can have when money and resources are invested into funding for community-based groups.

Today, William is one of nearly 40 people working on the Operations team at The Bail Project. This group represents the beating heart of the organization. Spread across the country, these staff members live – and have often been raised – in the same communities where they are advocating for pretrial and cash bail reform. Since launching six years ago, they’ve provided free bail assistance to more than 31,000 people who have returned to 91% of their court dates.

“The reform people are looking for… I knew back in 2014 that we were not going to get it right away. But I do believe we’ll eventually see it.”

Attitudes about crime, policing, and criminal justice reform became widespread in the wake of Michael Brown’s murder. Lawmakers across the country began discussing in earnest how to change racial inequities that have long been entrenched in the criminal justice system. William remembers telling people back then that people’s perspectives about the criminal justice system is like the swinging of a pendulum. “The reform people are looking for… I knew back in 2014 that we were not going to get it right away,” William said. “But I do believe we’ll eventually see it.”

Against this backdrop of personal and professional change, William has sought to converse more with local stakeholders in an effort to dispel misinformation and help ease tensions. “We’re here to keep conversations going,” William said. “And that to me means we’re keeping key [stakeholder’s] attention.”

Still, like many advocates working in this space, there came a time when William began to doubt whether reforming the criminal justice system was actually possible. Those doubts creeped in several years ago, when William’s son began making similar mistakes that he made when he was younger. “I remember picking [my son] up one day and crying in the car,” William said. “I told him I can’t watch him waste his life. And that if he continues, his parents would never be able to see him again on the outside.”

Still, like many advocates working in this space, there came a time when William began to doubt whether reforming the criminal justice system was actually possible. Those doubts creeped in several years ago, when William’s son began making similar mistakes that he made when he was younger. “I remember picking [my son] up one day and crying in the car,” William said. “I told him I can’t watch him waste his life. And that if he continues, his parents would never be able to see him again on the outside.”

William’s concerns about his son were short-lived. By demonstrating patience, vulnerability, and unconditional love, William helped his son turn his life around. Now, at age 32, William’s son has joined his father in fighting for criminal justice reform. “I talk to him everyday. About all sorts of things,” William said. “We’re best friends.”

As William gets ready to pass the baton to the next generation of change-makers, he remains steadfast that reform will ultimately prevail. He points to Trevor and the release on recognizance pilot program at the St. Louis County courthouse as one example of a collaborative program with judges that wouldn’t have been possible without the relationship building that has taken place in recent years.

“There’s finally a light on in the room. It’s not a bright light, but it’s a light that’s on,” William said. “And we’re here to keep conversations going.”

*Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the people involved.

Thank you for reading. The Bail Project is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that is only able to provide direct services and sustain systems change work through donations from people like you. If you found value in this article, please consider supporting our work today.